Queen Mudda

UNIT London

3 Hanover Square, Mayfair, W1S 1HD

26 March - 24 April 2021

“All Black women are Queens. This is the heart of the body of work presented by Cydne Jasmin Coleby for Queen Mudda – her celebratory and unabashed first solo show in London.”

– Natalie Willis, Curator.

Queens In Their Own Right

Cydne Coleby’s celebration of kin and Black Womanhood

By Natalie Willis, Editor-at-Large - The Caribbean, Burnaway Magazine, and curator of “Queen Mudda”.

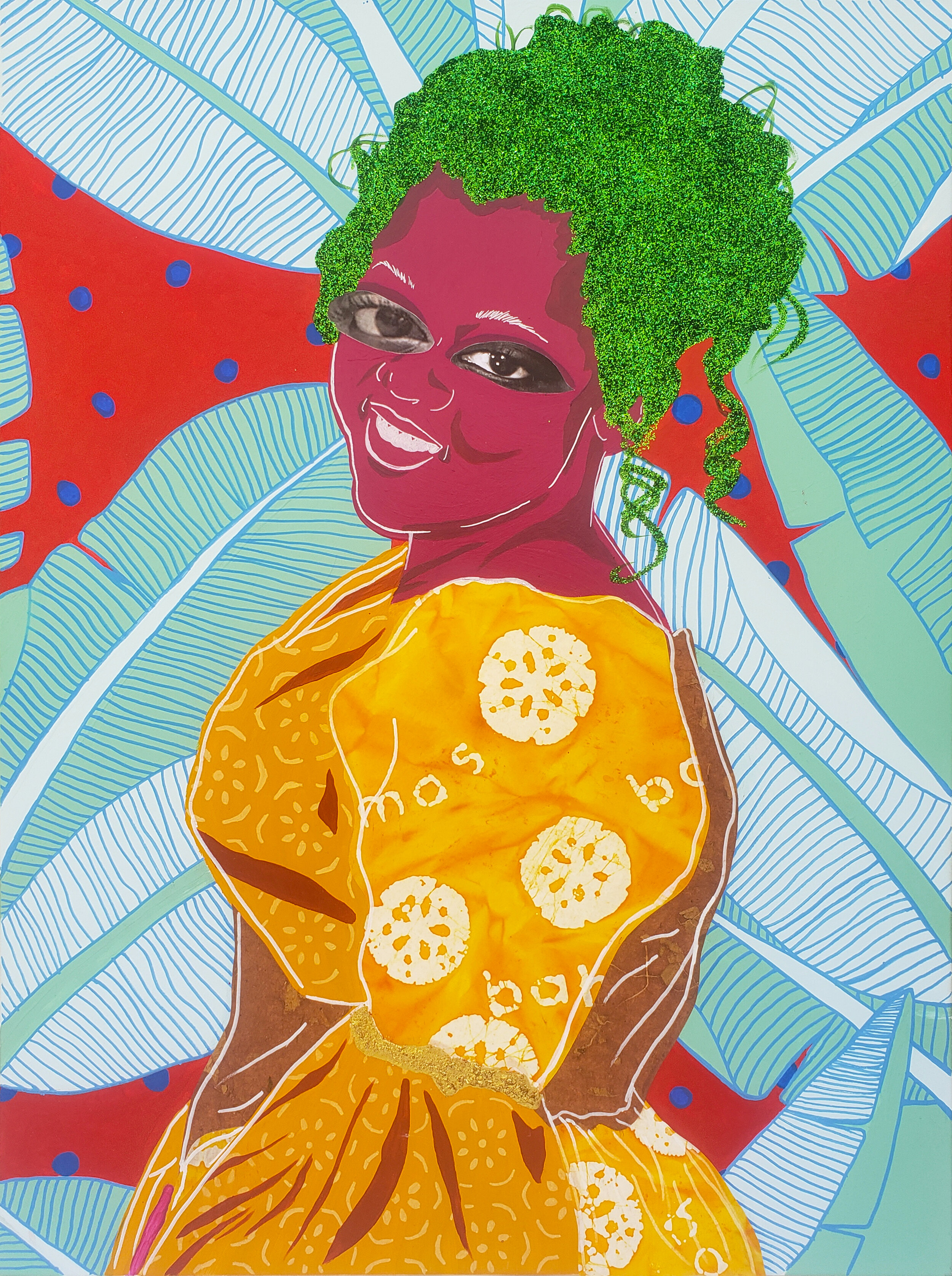

All Black women are Queens. This is the heart of the body of work presented by Cydne Coleby for “Queen Mudda” - her celebratory and unabashed first solo show in London. There is a severe exploitation of unseen labour in Black women the world over. In a time where we are contending with heightened issues around racism and the patriarchy, Coleby gives us a moment to consider the matriarchs of our family lines. “Queen Mudda” is a celebration of the women and girls in our families - those who truly have the broadest shoulders, who are the backbones of our family lines.

Using her family archives and storytelling, we are offered up a moment to consider the ways in which all mothers may be considered queens in their own right. With nods to Rococo, but also to the hyper-embellishment of the Caribbean and African diaspora, we are at once given the frills and ruffles of classic portraits of the ruling class in the Baroque period, alongside the vibrating patterns of African wax print fabric, Junkanoo, and Carnival. Performance is the undercurrent of this work: the performance of womanhood, of respectability, of being. In a world where being is appearing, Coleby offers the matriarchs of her family line the opportunity to appear as elevated as the care they give to their kin.

Coleby’s practice, first rooted in self portraiture and now extended into depictions of those in her bloodline, has consistently built traction on the idea of self-celebration, ownership, and self love via a re-imaging and reimagining of the self. As a Black Caribbean woman, that re-presentation of her image (and of her feminine family members) holds significant weight. It serves as a radical act in many respects, given the marginalization of Black women and simultaneous demonizing, oppression, and fetishization of Black womanhood throughout colonial histories. Most notably in Coleby’s oeuvre is the lack of deference to the tourist ideal of The Bahamas, an eschewing of what Dr Krista Thompson describes as “the picturesque” in her seminal text “An Eye For The Tropics”. Though there is a diasporic sense of familiarity in the images (for many of us from the Black Atlantic at the very least), Coleby is not serving up tropes, far from it. Much of the world is accustomed to thinking of and viewing people of The Bahamas, and the Caribbean at large, as beings in servitude - whether it is our colonial traumas around slavery and plantations, or their more contemporary legacies as service in hotels and resorts. “Queen Mudda” is an avowed departure from this, and in moving from ideas of service to the tourist public, she highlights the invisible labour of Black women in the domestic and family spaces.

Moreover, she is doing so with such joyousness at a moment when the media is rife with Black pain and trauma. “Queen Mudda”, from the playfulness of its title to the vibrating patterning, texture, and color of her work, is a balm and offers some tentative attempts to balance the current conversations on Blackness. There is deep seated pain and there is trauma, but so too is there opportunity to celebrate and “love on” those who are the most vulnerable both within and without our communities: Black Women.

The way that global narratives around Blackness and around Caribbeanness are shaped feel almost genetically rooted in the colonial gaze. How history is written the world over is problematic at best, but there is a profound difficulty in the Caribbean region around opportunistic and amnesiatic historytelling that leaves the contemporary descendents of formerly, forcibly displaced Africans in even more uncertainty and precariousness in relation to the formation of identity at both personal and national levels.

“Having no name to call on was having no past; having no past pointed to the fissure between the past and the present. That fissure is represented in the Door of No Return: that place where our ancestors departed one world for another; the Old World for the New. The place where all names were forgotten and all beginnings recast.” (Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return)

As Brand so deftly puts it, we can imagine both the pain and tentatively brave hopefulness in looking to the future, and an implication of an afrofuture. The function of the future, of the present, and past in Coleby’s work is collapsed into one - they are at once nostalgic renderings of times gone by within the family, but also of a vibrant present and the future lineage. History itself is a narrative, a story, something we take as truth and fact but which in actuality is woefully at the whim of the subjectivities and proclivities of the writer - and yet our displaced and re-placed Caribbean identities hinge upon this shifting sand of history. For Brand, in speaking of the simultaneous exit point of enslaved Africans in the continent and entryway into the Caribbean and the Americas, “The Door of No Return - real and metaphoric as some places are, mythic to those of us who are scattered in the Americas today. To have one’s belonging lodged in a metaphor is voluptuous intrigue; to inhabit a trope; to be a kind of fiction.” (Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return). In this thinking, history itself can be seen as a “kind of fiction”, and Coleby’s portraits become its retelling - she is authoring and authorizing a new narrative in her family’s (hi)story. It is a route and act of becoming on her own terms, through a careful sifting through her family archives - and so too are archives, as history, in their own a thing of fiction:

“Your archive is an expected declaration – a pronouncement that makes manifest your worth and belonging in the great halls of higher learning. The archive, it must be noted, is also your enabling fiction: it is the thing you say you are doing well before you are actually doing it, and well before you understand what the stakes are of gathering and interpreting it.” - Julietta Singh, No Archive Will Restore You

Coleby seeks not to restore Black women to their inherent glory, she is rebuilding it entirely from the ground up. With collage elements of her own face inserted into those of the women who came before her and after her, she reflects not only on ideas of ancestry and matrilineage, but also of her future survival by blood in these women who have cared for her and whom she has also cared for in return.

The hyper-embellishment and patterning of the work are an act of love indeed: the time intensive cutting of crepe paper for Junkanoo inspired fringes, of laying paint to canvas in someone’s image. They are, also, an act of rebellion and most importantly of visibility. In a world oversaturated with digital and social media presence - that we are all painfully aware of at present in this pandemic - to “be” is to appear. Coleby’s act of heightening the visibility of her family - often dressed in their best, poised, elegant, radiant images of the ideal of the feminine - is partial protest to the historic exclusion of Black women in classic portraiture. It also contains the rebellion-roots of Junkanoo, a culturally significant street celebration with elaborate costumes constructed of cardboard, crepe paper, and feathers that has its origins in the subversive protest of enslaved Africans. In many ways, through Coleby’s excellent use of color and patterning in ensnaring our vision in this very weary attention economy, “these forms translate approaches to visibility, namely the efficaciousness of the effect of light and the prestige of the frame of representation.” (Krista Thompson, Youth Culture, Diasporic Aesthetics, and the Art of Being Seen in The Bahamas). She forces the eye to gaze upon these women, who would be deemed “ordinary” under many global standards, to see the richness of spirit residing in each and every one of them. No longer are they only revered or loved by their family, they are now presented to us in near-debutante fashion for us to look upon and offer up appreciation and praise.

“Queen Mudda” is a joyous and almost ancestral practice in honoring the love and labour of Black women, of herself.

Crowning Ceremony, 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, crepe paper, sand, gold in and photo collage on canvas

152 x 122 cm

Queen in Training, 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, crepe paper, fabric, and photo collage on canvas

102 x 91 cm

Church Mudda, 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, gold ink, glitter and photo collage on canvas

102 x 91cm

Heir Lesley (Her Mudda’s Shadow), 2021 Acrylic, decorative paper, glitter, androsia fabric, and photo collage on canvas

102 x 76 cm

Mudda Pat, 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, glitter and photo collage on canvas

102 x 76 cm

Rebel Princes (free from the weight of that crown), 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, glitter, androsia fabric, and photo collage on canvas

102 x 76 cm

Sweet Youth (Patricia I), 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, fabric, crepe paper, gold ink and photo collage on canvas

122 x 76 cm

Blossomed (Patricia II), 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, androsia fabric, and photo collage on canvas

122 x 76cm

Courted Laydees, 2021

Acrylic, sand, watercolor, glitter, decorative paper and photo collage on canvas

122 x 152 cm

Thea in The Garden, 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, gold ink, glitter and photo collage on canvas

152 x 122 cm

High Point, 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, sand, gold ink and photo collage on canvas

122 x 76 cm

Ushered In, 2021

Acrylic, decorative paper, crepe paper, glitter, gold ink and photo collage on canvas

97 x 91 cm